NAVAL

POSTGRADUATE

SCHOOL

MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA

THESIS

|

Approved for public release;distribution is unlimited

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

NAVAL

POSTGRADUATE

SCHOOL

MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA

THESIS

|

Approved for public release;distribution is unlimited

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

NSN 7540�01�280�5500������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Standard Form 298 (Rev. 2�89)

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Prescribed by ANSI Std. 239�18

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

Approved for public release;distribution is unlimited

CYBER-WARFARE: JUS POST BELLUM

Maribel Cisneros

Captain, United States Army

M.A., Webster University, 2013

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN CYBER SYSTEMS AND OPERATIONS

from the

NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL

March 2015

Author:����������������������� Maribel Cisneros

Approved by:������������� Neil C. Rowe

Thesis Advisor

Wade L. Huntley

Second Reader

Cynthia E. Irvine

Chair, Cyber Academic Group

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

ABSTRACT

There is a lack of attention to the aftermath of a deployed cyber weapon: There is no mechanism for the assignment of accountability for the restoration of affected infrastructure and remediation of violation of established laws of war after cyberattacks occur.� This study analyzes International Humanitarian Law and international treaties as they apply to the cyber post-conflict period and explores current jus post bellum frameworks which can be used to design a cyber-warfare jus post bellum framework.� It also analyzes analogies to traditional warfare in the damage assessment and aid provided during the recovery period of the 1998 Kosovo and the 2003 Iraq Wars.� It also discusses the available international cyber organizations. As an example, the study analyzes responses to cyberattacks in a case study involving South Korea and North Korea.

Additionally, this study examines the related issues of the effects of deploying a cyber-weapon, the ways to establish acceptable levels of attribution, the challenges of cyber-damage assessments, and the ability to contain and reverse cyberattacks.� This thesis proposes a cyber-warfare jus post bellum framework, with emphasis on prevention and cyber weapons control, proposes cyberattack relief-effort actions, and offers a post-cyberattack cost checklist.

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I.������������ INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................... 1

A.���������� CYBER-WARFARE: JUS POST BELLUM FRAMEWORK DEVELOPMENT JUSTIFICATION........................................................................................... 2

B.���������� THESIS PURPOSE......................................................................................... 4

C.���������� THESIS OUTLINE......................................................................................... 5

II.���������� BACKGROUND......................................................................................................... 7

A.���������� INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW........................................... 7

B.���������� JUS POST BELLUM...................................................................................... 9

C.���������� JUS POST BELLUM IN CYBERSPACE................................................. 14

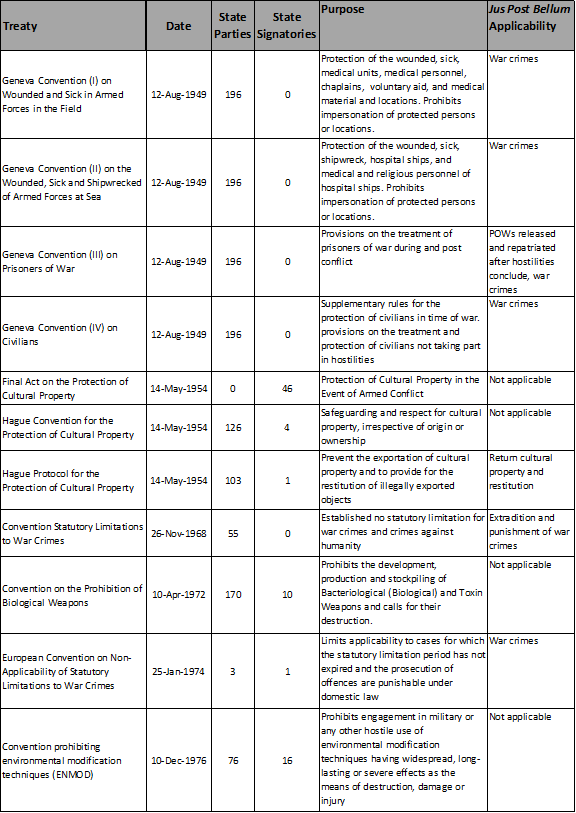

D.���������� TREATIES AND ARTICLES APPLICABLE TO JUS POST BELLUM 17

1.����������� Hague Conventions............................................................................ 18

2.����������� Geneva Convention:.......................................................................... 18

3.����������� Conventions Prohibiting Certain Conventional Weapons............. 18

4.����������� Additional Treaties Prosecutable for War Crimes......................... 19

5.����������� Genocide............................................................................................. 19

6.����������� Mercenaries........................................................................................ 19

7.����������� Additional Rights Violations............................................................. 19

8.����������� UN Charter........................................................................................ 19

a.����������� Article 39................................................................................. 20

b.����������� Article 51................................................................................. 20

c.����������� Article 92................................................................................. 20

d.����������� Article 94................................................................................. 20

9.����������� Statue of the ICJ................................................................................ 20

a.����������� Article 36................................................................................. 20

b.����������� Article 38................................................................................. 21

c.����������� Article 41................................................................................. 21

10.�������� ICC...................................................................................................... 21

11.�������� NATO................................................................................................. 21

E.���������� CONCLUSION.............................................................................................. 22

III.�������� CyberAttacks................................................................................................... 23

A.���������� TYPE OF CYBERATTACKS.................................................................... 24

B.���������� CYBERATTACK VECTORS.................................................................... 26

C.���������� CYBERATTACK EFFECTS..................................................................... 28

D.���������� Cyber-Weapon Damage Assessment....................................... 30

E.���������� ATTRIBUTION............................................................................................ 32

F.���������� CONTAINABILITY AND REVERSIBILITY OF CYBER WEAPONS 35

G.��������� CONCLUSION.............................................................................................. 36

IV.�������� Past Kinetic Operations............................................................................ 39

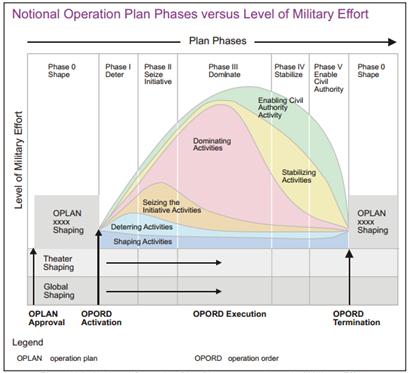

A.���������� Stability operations....................................................................... 39

B.���������� Damage Assessment KINETIC Versus CYBER....................... 41

1.����������� Jus Post Bellum Cost......................................................................... 42

2.����������� Entities involved in Reconstructions................................................. 46

a.����������� 2003 Iraq War......................................................................... 46

b.����������� 1998 Kosovo War.................................................................... 47

C.���������� international cyber organizations................................... 48

D.���������� Conclusion.............................................................................................. 50

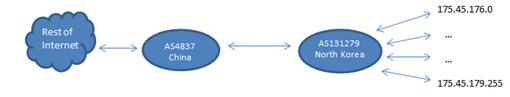

V.���������� CASE STUDY: NORTH KOREAN CYBERATTACKS.................................... 53

C.���������� NORTH-KOREA SUSPECTED CYBERATTACKS............................. 57

1.����������� July 2004............................................................................................. 58

2.����������� August/September 2005..................................................................... 58

3.����������� July 2006............................................................................................. 58

4.����������� October 2007...................................................................................... 58

5.����������� September 2008.................................................................................. 58

6.����������� Mar 2009............................................................................................. 59

7.����������� July 2009............................................................................................. 59

8.����������� November 2009.................................................................................. 59

9.����������� January, March, and October 2010................................................. 60

10.�������� March 2011......................................................................................... 60

11.�������� 2012..................................................................................................... 60

12.�������� June 2012............................................................................................ 61

13.�������� March 2013......................................................................................... 61

14.�������� June 2013............................................................................................ 62

15.�������� November 2014.................................................................................. 62

D.���������� ATTRIBUTION Analysis of THE Attacks................................. 63

E.���������� ANAlYSIS.................................................................................................... 67

1.����������� Damage Costs..................................................................................... 68

2.����������� Establishing Attribution.................................................................... 68

3.����������� Cyberattack Responses..................................................................... 70

F.���������� Conclusion.............................................................................................. 72

VI.�������� Recommendations.......................................................................................... 75

A.���������� CYBER-WARFARE JUS POST BELLUM FRAMEWORK................ 75

1.����������� Outlaw Unethical Cyber Weapons................................................... 75

2.����������� Add Critical Cyber Infrastructure to the Protected Sites.............. 76

3.����������� International Community Involvement............................................ 77

4.����������� Accountability.................................................................................... 78

a.����������� Punishment............................................................................. 78

b.����������� Restoration of Affected System and Infrastructure................ 79

c.����������� Proportionality......................................................................... 79

5.����������� Plans.................................................................................................... 80

B.���������� CYBERATTACK RESPONSE.................................................................. 80

1.����������� Step 1: Information Gathering......................................................... 81

2.����������� Step 2: Cyberwar............................................................................... 81

3.����������� Step 3: International Notification..................................................... 82

4.����������� Step 4: Formal Investigation............................................................. 82

5.����������� Step 5: Attribution............................................................................. 82

6.����������� Step 6: Cyberattack Response.......................................................... 83

7.����������� Step 7: Recovery................................................................................ 83

a.����������� Cost Assessment...................................................................... 83

b.����������� Vulnerabilities Elimination..................................................... 85

c.����������� Anti-malware Signatures........................................................ 86

d.����������� Restoration.............................................................................. 86

e.����������� Incident Response Planning................................................... 86

f.������������ Education................................................................................ 87

VII.������ Conclusion.......................................................................................................... 89

A.���������� SUMMARY................................................................................................... 89

B.���������� FUTURE WORK.......................................................................................... 91

appendix A. Current International Agreements............................... 93

APPENDIX B. CYBERATTACK CHECKLIST EXAMPLE....................................... 99

List of References................................................................................................... 101

initial distribution list...................................................................................... 113

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.������������ Advanced Persistent Threat (from Symantec, 1995)....................................... 26

Figure 2.������������ Mission Cyber Security Assessment Process (from Jakobson, 2011).............. 31

Figure 3.������������ Evidence transfer physical and digital dimensions (from Casey, 2011).......... 34

Figure 4.������������ Phasing Military Operations (from DOD, 2011a, p. V-6)............................... 40

Figure 5.������������ Cost Framework for Cyber Crime (from PI, 2013)......................................... 45

Figure 6.������������ Key Intergovernmental Institutions (from Ferwerda et al., 2010).................. 49

Figure 7.������������ North Korea Internet Footprint (after APNIC, 2014)..................................... 55

Figure 8.������������ Timeline of executable file download events over HTTP� (from Dell SecureWorks, 2013). 65

Figure 9.������������ Four years of Dark Soul (from Symantec, 2013)............................................. 66

Figure 10.��������� Cyberattack Response Flowchart.................................................................... 81

Figure 11.��������� Cyberattack Cost Checklist� (after Booz Allen Hamilton Inc., 2014; and PI, 2013).����������� 85

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1.�������������� International Body Responsibilities� (after ICRC, 2014; UN, 1945; ICC, 1998).���� 8

Table 2.�������������� Iraq War Operation Cost (after Belasco, 2014)............................................... 43

Table 3.�������������� Kosovo War Cost (after Ek, 2000).................................................................. 44

Table 4.�������������� North Korea Cyber Elements (after Brown, 2004; Clarke & Knake, 2010;� Sang-Ho, 2014a).������� 56

Table 5.�������������� Percentage of Individuals Using the Internet-South Korea versus� North Korea (after ITU, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau, 2013)...................................................................................... 67

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

API���������������������������� Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions of 1949

APT���������������������������� advanced persistent threat

AS������������������������������ autonomous system

BDA�������������������������� battle damage assessment

CCDCOE������������������ Cooperative Cyber Defense Centre of Excellence

CCW�������������������������� Certain Conventional Weapons

CERT������������������������� Computer Emergency Response Team

CRS��������������������������� Congressional Research Services

CTU��������������������������� Counter Threat Unit

DDoS������������������������� distributed denial of service

DoS���������������������������� denial of service

DPRK������������������������ Democratic People�s Republic of Korea

ENISA����������������������� European Network and Information Security Agency

EU������������������������������ European Union

FBI����������������������������� Federal Bureau of Investigation

FIRST������������������������ Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams

FY������������������������������ Fiscal Year

ICC���������������������������� International Criminal Court

ICJ����������������������������� International Court of Justice

ICRC������������������������� International Committee of the Red Cross

IHL ��������������������������� International Humanitarian Law

IMPACT�������������������� International Multilateral Partnership against Cyber Threats

IP������������������������������� Internet Protocol

ISIL��������������������������� Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

ITU���������������������������� International Telecommunication Union

LOAC������������������������ Law of Armed Conflict

OS������������������������������ operating system

POSTECH����������������� Pohang University of Science and Technology

POW�������������������������� Prisoner of War

MBR�������������������������� master boot record

NATO������������������������ North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NIS���������������������������� South Korea National Intelligence Center

OECD������������������������ Organization for Economic Co-operations and Development

ROK�������������������������� Republic of Korea

SPE���������������������������� Sony Pictures Entertainment

UN ���������������������������� United Nations

USB��������������������������� universal serial bus

WSIS������������������������� World Summit on the Information Society

WWII������������������������� World War II

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank my husband, Jimmy, for the unwavering love and support that he has shown our babies, Luke and Leia, and me during our time at the Naval Postgraduate School and throughout my military career.� I want to thank my mother, Ofelia Cisneros who, as a single mother of three, always placed the welfare of her children first and taught us honesty, hard work, and determination.

I would also like to thank my advisor, Dr. Rowe, as this work would not have been possible without his contributions, helpful feedback, and guidance throughout the thesis learning process. �Last, but not least, I would to thank Dr. Huntley for his insightful comments and assistance with this paper.

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

Certain it is that a great responsibility rests upon the statesmen of all nations, not only to fulfill the promises for reduction in armaments, but to maintain the confidence of the people of the world in the hope of an enduring peace. (Kellogg, 1929)

States are developing cyber weapons.� Cyber weapons can target systems anywhere around the world because we have a global interconnected network.� Industrialized and developing states dependence on cyberspace and the Internet have turned these tools into �global commons� (Giesen, 2013); however, these tools also provide the conduits for attacks.� Any state can target the military organizations of other states through cyberspace and from their operations centers.� Considering the Internet�s interconnectedness, these cyberattacks can also produce significant destruction (Giesen, 2013) which could even result in loss of life as a secondary effect.

Not only government organizations use cyberspace; the private sector, civilians, and academia employ the same resources that cyberspace provides such as the power grid.� Therefore, cyberattacks can cause civilian entities to end up being collateral damage.� The damage cyber weapons can cause these various organizations can be just as dangerous and costly as kinetic weapons.� Consequently, when actors in cyberspace deploy cyber weapons, they should also bear the responsibility of support during the affected infrastructure�s restoring and rebuilding phases.� This transition phase is known as jus post bellum or justice after war.� There needs to be planning for the aftermath of cyberattacks in addition to controlling proliferation of cyber weapons.� This is especially important when state and non-state actors continue to deploy more sophisticated cyberattacks with no accountability, such as Stuxnet (2010) (Zetter, 2011), the cyberattacks against Estonia (2007), Georgia (2008) (Kaska, Talih�rm, & Tikk, 2010), and South Korea (2013) (Sang-ho, 2014a).� These attacks had no direct financial-gain intentions, but were intended to destroy or disrupt the selected targets, and were possibly conducted or at least sponsored by state actors.

�����������

States enter into agreements and treaties to ensure adherence to established laws of war, aid the safety of their citizens, and provide humane treatment for their warfighters during armed conflict.� As the international community develops new weapons, it also proposes and enters into new agreements such as those on the development and use of nuclear weapons.� With the emergence of cyber weaponry and the risk cyberattacks pose to civilian populations, the international community needs to use the same international-agreement paradigm to control cyber-weapon development and ensure ethical conduct during and after cyberwars.

States are supposed to plan for jus post bellum activities when they enter into an armed conflict. However, even with adequate planning, states underestimate the scope of the post-conflict actions, which results in failed attempts to conduct proper post bellum activities. For example, the United States government expected a swift transition during the 2003 Iraq War, with a fast military departure after they established the new government; this was not the case and it showed the lack of consideration for post bellum activities (McCready, 2009).� During an armed conflict, militaries� main objective is to win wars; therefore, they often misjudge stability operations and believe that, once the fighting concludes, the stability operations will be easy to accomplish.� For instance, previous wars degraded Iraq�s infrastructure; the 2003 Iraq War caused further destruction to food, water, security, and sanitation infrastructures, which considerably increased death rates (Burnham, Doocy, Dzeng, Lafta, & Roberts, 2006).� This made post bellum actions harder to accomplish and greatly affected the ability to save lives and quickly reconstruct infrastructure.� Orend (2007) believes that there is great uncertainty as to whether or not Iraq is better than it was before the 2003 war.� This could be true since they are currently facing an occupation by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).� ISIL took advantage of the void the U.S. and its coalition partners left before Iraq�s full war recovery.� If we cannot correct the situation with kinetic operations that have plethora of historical learning lessons, it will be even more difficult to get it right in cyberspace and to properly deal with the aftermath of cyberwars.� There are still many uncertainties when releasing cyber weapons, and decision makers have limited understanding of the technology and ability to determine what the collateral damage will be.

Some weapons continue to cause harm many years after a war has ended.� For example, minefields are still hurting local populations because they are either never removed or their locations are unknown (U.S. Department of State, 1994).� States may need to deal with these types of issues for many years.� The implications of releasing a computer virus have some similarities since a virus can continue to affect systems even after the conflict has ended, and it encounters many victims on its path that might not have the capabilities to respond.� For instance, the Stuxnet worm, one of the most precise cyber-weapon released to date, targeted the Natanz facility (Zetter, 2011) and had direct collateral damage on many civilian machines as well as the indirect damage caused as a result of criminals using the source code to create virus variations for their own crimes (Lin, Allhoff, & Rowe, 2012).� The damage might not equate to loss of human life; nonetheless, when a virus is involved, it affects many systems within seconds and may require millions of dollars to assess the damage and fix the problem.� The cost depends on the number of affected systems, the labor hours required, and the required level of technical knowledge of those involved in the effort.� A computer virus deployment thus raises ethical issues concerning state and non-state actors, whether attacks adhere to the laws of war, assessment of the cost to public and private organizations, and attribution.�

States and the international community have established laws to deal with cyber crime, but what happens when these cyberattacks are not of a criminal nature?� How do states and the international community deal with this emerging threat?� The international community has not come to a consensus about what constitutes an act of war in cyberspace.� They have given even less thought to what should happen after cyber conflict.� This study analyzes International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and international treaties as they apply to after cyber conflict, explores current jus post bellum frameworks, analyzes the aid provided during the recovery period during two kinetic wars, and discusses the available international cyber organizations.� All these concepts are used as a basis to design a cyber-warfare jus post bellum framework.

Vint Cerf stated in 2011, �the Internet is brittle and fragile and too easy to take down� (cited in Karlgaard, 2011).� What he means is that any malicious actor with a connection to the Internet has the ability to cause harm in cyberspace.� Many cyber systems such as industrial control systems are vulnerable because security was not a priority in the design process.� One example is the Aurora vulnerability, which targets a sequence of electrical breakers to get them out of synchronization, which can make a system break down and cause physical damage; this vulnerability is still present today in many control systems (Zeller, 2011).� States and non-state actors can target electrical systems from far away as the electric and other control systems continue to move their access to the Internet.� States will continue to need cyber protection from aggressors and ensured justice.

The international community can seek to learn from previous examples and researchers� jus post bellum concepts to start the discussion on what a just peace looks like in dealing with cyber post-conflict.� There are good examples of post bellum actions such as for World War II (WWII) where there was a positive outcome by fully considering post-conflict actions (McCready, 2009).� The U.S. began post conflict planning during WWII almost at the beginning of the war and continued planning until the end of the war (McCredy, 2009).� The U.S. used various entities to deal with post-conflict actions.� Advance planning facilitated international cooperation to ensure proper actions for reconstruction and restoration and the establishment of a government.� Some specialists, Orend (2007) and McCredy, advocate for states to pledge their jus post bellum activities and to make them an essential part of war planning. �Then, the international community can hold states accountable if they fail to follow the promised post bellum actions.� In the same way, the establishment of the proper cyber-warfare jus post bellum actions will help during post-conflict resolution.� A cyber post-conflict framework before a major cyber conflict occurs will limit human suffering, and provide the steps for fast response, investigations, and accountability.

As the opening quote states, it is the responsibility of all states to ensure everlasting peace.� Consequently, this study provides a framework for cyber post-warfare conduct, with emphasis on prevention and cyber weapons control.� Additionally, the study examines the implications of deploying a cyber-weapon in terms of its reversibility, attribution, and planning of a cyber relief effort.

This thesis consists of seven chapters.� Chapter I introduces the study�s justification and the purpose.� Chapter II defines IHL, current jus post bellum frameworks, and the treaties applicable to cyber jus post bellum.� Chapter III surveys cyberattacks, attack vectors, cyberspace damage assessment, the effects of previously deployed cyberattacks on military, civilians, and private organizations, and the ability to contain and reverse them.� Chapter IV discusses damage assessment for past kinetic operations, the organizations involved in the recovery effort, and available international cyber organization that can provide support during cyber conflicts.� Chapter V analyzes responses to cyberattacks in a case study involving South Korea and North Korea.� Chapter VI presents a cyber-warfare jus post bellum framework, proposes a cyberattack relief-effort flowchart, and offers a post cyberattack cost checklist.� The thesis concludes with a summary and recommendations for future work.

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

War often leads to the dissolution of established governments and civil order, and the destruction of critical elements of a society�s infrastructure, and this dissolution or destruction may result in the post bellum suffering or death of many in the defeated society. Victors have a moral obligation to ensure the security and stabilization of a defeated nation. Whenever practical and possible, they must provide the essentials of life (food, clothing, shelter, medicine, etc.) to those without them and repair or rebuild infrastructure essential to a vulnerable population�s health and welfare. (Iasiello, 2004, p. 42)

After Henry Dunant witnessed the bloodshed of the Battle of Solferino in 1859, he started the movement to establish the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to aid the wounded (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2013).� Swiss citizens founded the ICRC in 1863, which later became the overseer of International Humanitarian Law (IHL), based on the Geneva and Hague Conventions (ICRC, 2002).� The purpose of IHL is to provide suggested principles for states to enter into legal international contracts in the forms of treaties, declarations, or agreements which will provide protection during conflicts to civilians and personnel not participating in hostilities; it also restricts what weapons can be used (ICRC, 2002).� However, not all states have ratified all the current IHL treaties and do not have to abide by the treaties they do not ratify; therefore the international community has customary international law, which binds all states (Henckaerts & Doswalk-Beck, 2005) to respect these customary international laws.� As a result, the international community can find states in violation of customary law or established IHL treaties whether states are signatories of the treaties or not.� Other international bodies involved in the preservation of international law are the United Nations (UN), the International Court of Justice (ICJ), and the International Criminal Court (ICC). �These bodies and their responsibilities are depicted in Table 1.

|

International Body |

Responsibility |

|

United Nations |

Maintains and Restores Peace |

|

���� General Assembly |

Votes on new resolutions |

|

���� Security Council |

Maintains peace and restores peace, issues sanctions and measures |

|

���� ICJ |

Enforces Customary International Law as the UN judicial body, manages state level jurisdiction, conducts investigations |

|

ICRC |

Oversees International Humanitarian Law (Hague, Geneva, and other treaties), provides assistance during and post conflicts |

|

ICC |

Prosecutes war crimes, genocides, acts of aggression, crimes against humanity, manages individual or organizational level jurisdiction |

Table 1.�

International Body Responsibilities

(after ICRC, 2014; UN, 1945; ICC, 1998).

The UN is an international body created after World War II, which also requires states to abide by international law as part of its charter (UN, 1945). �The General Assembly of the UN adopted resolutions to protect human rights during armed conflict and peace, to include establishing ad hoc courts to deal with human rights violations (Gasser, 1995).� The Security Council is a branch of the UN that establishes steps to ensure or reinstate peace while ensuring human-rights protection (Gasser, 1995).� The ICJ, which does not specifically address IHL, is the UN prosecution body to ensure states abide by international conventions and customary law (ICJ, 2015). �The ICC is a judicial international body that specifically qualifies certain violations as war crimes (ICC, 1998).� Essentially, states are supposed to abide by these customary laws during the conduct of armed conflict to avoid unnecessary suffering and to protect civilians, the wounded, prisoners of war (POWs), civilian infrastructure, and children; if not the international organizations can hold states and individuals accountable for war crimes (Henckaerts & Doswalk-Beck, 2005). �States can use the ICJ and ICC to bring issues or IHL or customary international law violations against other states, individuals, or organizations and ensure war crimes are brought to justice (ICJ, 2015; ICC, 2014).� The judges assigned to the ICC must have knowledge of criminal law, law procedures, IHL, and the law of human rights (ICC, 2014).

The ICRC, as the overseer of IHL, attempts to maintain IHL current with newly invented technology and warfare weapons to avoid unnecessary suffering.� This was the case when the ICRC updated IHL to include treaties prohibiting the use of chemical weapons, including their �development, production, and stockpiling� (ICRC, 2002, p. 11).� However, D�rmann (2001) argues that IHL is not weapon-dependent. �

Currently there has been much discussion about how to translate IHL into the newly defined cyberspace domain.� Harold Hongju Koh, a United States Department of State Legal Advisor, has said the U.S. government believes that the principles of international law apply to cyberspace (Koh, 2012). �More recently, the Tallinn Manual, published by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Cooperative Cyber Defense Centre of Excellence, proposed that established customary international laws apply to cyber-warfare (Schmitt, 2013).� Nevertheless, there are challenges to ensure an ethical cyberwar, such as possible collateral damage due to computer-system interconnectedness and the difficulty of attribution and damage assessment (Liaropolous, 2010).� For example, one of those international rules is to distinguish between combatants and non-combatants in targeting, which raises questions due to links between civilian and military systems and the inability to contain a computer virus to a specific target.�

Furthermore, the Tallinn Manual, IHL, and customary laws do not address the steps states should take after the conclusion of war or after states carry out a cyberattack, except for prosecution of war crimes violations (Schmitt, 2013; Henckaerts & Doswalk-Beck, 2005). Just as there are rules for the ethical consideration of the start ( jus ad bellum) and conduct ( jus in bello) of cyber armed conflict, we propose here that there should be rules for the ethical termination of a cyber armed conflict: jus post bellum�transition from war to peace.

IHL is guidelines for states to conduct righteous and ethical war.� It attempts to ensure states remain within the legal framework during war, then referred to as just war.� Just-war theory measures a state�s right to go to war (jus ad bellum criteria) and states� conduct during war (jus in bello criteria) (Douglas, 2003).� The jus ad bellum criteria are just cause, right intention, right authority, reasonable hope of success, last resort, announcement of intention, and proportionality (Douglas, 2003). �The jus in bello criteria are right intention, proportionality, and discrimination (Douglas, 2003). �There has been much discussion of the frameworks of jus ad bellum and jus in bello. �The international community must start to think about the ethical and moral actions states should take after a war has concluded.� Since just-war theory or IHL does not provide a framework for justice after war, scholars advocate that jus post bellum is a critical pillar of just war and should not be ignored (Bass, 2004; Douglas, 2003; Orend, 2007; �sterdahl, 2012; McCready, 2009).� These theologists, scholars, and ethicists introduced a framework known as jus post bellum theory. �This phase consists of the actions states take to ethically end wars and transition to peace.

Immanuel Kant is the first philosopher thought of as the founder of viewing warfare as consisting of three different pillars: �1. the right of going to war; 2. right during war; and 3. right after war� in his Metaphysics of Morals (cited in Stahn, 2006, p. 935).� Kant also expressed in his Toward Perpetual Peace, as translated and publish by Yale University Press, that states involved in armed conflict should not conduct acts that will prohibit them from being able to reach peace (Kant, 2006). �As an example, Kant (2006) believed that peace agreements that had ulterior motives should be invalid as is it not a peace agreement and it only postpones a new inevitable war.� Additionally, Kant believed that a state�s military superiority did not mean it could punish or force the defeated to recompense the victor (cited in Stahn, 2006).

Douglas (2003) believes just-war criteria are outdated and should be revisited for current times. �Douglas contends that states go through a moral deliberation when starting and conducting a war and he advocates for the same moral deliberation during the termination of war, what he calls �just result.�� Douglas also believes that just-war theory has not provided adequate criteria for jus post bellum and this could result in more hostilities. �Moreover, Douglas believes that humanitarian relief can limit war impacts and the possibility of new conflict.

Orend (2007) believes that jus post bellum has been mainly ignored due to tradition and because many just-war theorists include it as part of jus ad bellum.� Orend does concede that there should be a strong link between jus ad bellum and jus post bellum, but he also advocates for much more and therefore it should be a phase by itself of the just war framework, which should be based on Kant�s concepts. �Additionally, Orend advocates for a jus post bellum Geneva Convention that stipulates, �what the winners of war may and may not do to countries and regimes they have defeated� (p. 575).� Orend proposes the following principles: rights vindication (human rights secured), proportionality and publicity (fair and public peace settlements), discrimination (distinction), punishment (hold aggressors accountable), compensation (possible mandated economic restitution), and rehabilitation (reconstruction). �Essentially, he believes states should plan and have strategies for an ethical war transition.� He stresses the benefits everyone will obtain with a set of established rules and measures, especially for difficult scenarios. �He ascertains that these procedures will be worth it for the victors, defeated, and international community as a whole.

Bass (2004) believes that jus post bellum aids states to focus the war.� Bass focuses on three central questions relevant to postwar behavior.� The questions are:�

What obligations are there to restore the sovereignty of a conquered country and what limitations do these obligations impose on states� efforts to remake the governments of vanquished countries? What are the rights and obligations that belligerent states retain in the political reconstruction of a defeated power? Are these rights limited to the reconstruction of genocidal regimes, or can a case be made for the political remaking of less dangerous dictatorships? [And] What obligations might victorious states have to restore the economy and infrastructure of a defeated state? Conversely, do victorious states have a right to demand some kind of reparation payments from defeated states who were aggressors in the concluded war? (Bass, 2004, p. 385)

These are important questions to consider during post-war conduct to ensure a moral and ethical post war behavior and long lasting peace.� Bass concluded that there are moral duties of victors when returning to peacetime; victors should exit immediately, unless it is a genocidal state in which case victors have a responsibility to aid in political reconstruction, and advocates for �prudence and proportionality� for reparations between victors and aggressors. �Those moral duties might include not leaving immediately, as some states might require the victor to remain in place and aid in reconstruction of government entities and physical infrastructure.

Iasiello (2004) also agrees that the jus post bellum is undeveloped and its examination can save lives, especially in a time of assured and immediate victories.� Iasiello proposes having a plan and vision for war termination, which will ensure actions to rebuilt, restore, and reestablish are not broken and abide by legal and moral guidelines. �Iasiello introduces seven criteria for post-conflict standards of behavior: �a healing mind-set, just restoration, safeguards for the innocent, respect for the environment, post bellum justice, the transition of warriors, and the study of the lessons of war� (Iasiello, 2004, p. 40). �All seven criteria are important for a peace-to-war transition. �Additionally, Iasiello proposes a three-stage interrelated approach to just restoration to allow for healing: protectorship (protect and provide for the victor and defeated populace), partnership (victor and defeated work together to restore, rebuild, and repair), and ownership (establish self-governance and sovereignty). �Just restoration highlights the importance of victors not leaving the defeated in a state of disarray and destruction. �It is the victor and defeated responsibility to ensure cooperation to ensure an eventual return to normal or better.

Boon (2005), unlike the previous authors, believes that a link between jus ad bellum, jus in bello, and jus post bellum is not necessary.� Boon advocates that the reason for war and how the war was fought should not affect the actions taken after war, which must still abide by justice principles.� In addition, Boon highlights �the central tasks of post-conflict reconstruction: the establishment of law and order, preparation for free elections, establishment of the groundwork for independent institutions and the recognition of fundamental rights and liberties with the aim of eventual self-governance� (p. 290�291). �To accomplish these task, Boon introduces three concepts: trusteeship (ethical and legal obligations to act in the best interest of the occupied state), accountability (hold people accountable for their actions), and proportionality (ability to assess the magnitude of legal intervention). �Boon argues that a link is not necessary for ethical post-war conduct, especially for states that did not have the right to go to war or did not fight ethically:� The international community should hold those states responsible for their unethical actions, but not excuse them from their responsibility in transitioning from peace to war ethically because they did not fight a just war.

�sterdahl (2012) concludes that even though there is already law to ensure jus post bellum in combination with peace agreements, there is still a void within these laws to effectively establish peace after a war has concluded.� Therefore, �sterdahl believes that war-to-peace transitions require a jus post bellum methodology and transitioning tools.� �sterdahl also concludes there is a need for law specific to jus post bellum, but that governments might be against establishing it because of the complexity and the requirements to fulfill a transition from peace to war.� Even though transitioning from war to peace can be a difficult task and event dependent, there are generalities that can be established to restore the peace.

Stahn (2008) believes that the international community has largely ignored the transition period from war-to-peace. �Stahn agrees with �sterdahl that current law is insufficient for jus post bellum, but also that it needs to be used to regulate the war-to-peace transition and not just as a moral slogan.� Stahn argues that jus post bellum can essentially set rules and limitations for local and international actors.� Stahn advocates for viewing jus post bellum as a whole by using established war-to-peace transition guidelines and their relationship. �Stahn also states that due to the complexity of current wars, jus post bellum should also apply to �events other than classical wars,� as well as be defined case-by-case because of the inability to have a clear understanding of the end of hostilities (pp. 333�334). �Stahn does a good job highlighting that every war is different and the transition should be war-specific. �The ability to develop additional guidelines for each war can expedite the transition.

James Turner Johnson argues that the aftermath actions are included and should be planned during the jus ad bellum phase (cited in McCready, 2009, p. 67). �McCready (2009) disagrees with Johnson and argues that there needs to be a separate set of criteria to cover jus post bellum.� He explains that jus post bellum is a misleading term as it is difficult to transition from war to peace due to major operations concluding and transition beginning before war is completely over. ��The intent of establishing a jus post bellum category is to determine beforehand what these war-related responsibilities should be after the shooting stops and who should be responsible for them� (McCready, 2009, p. 68).� McCready appeals for a set of guidelines that can ensure states are aware of their post-conflict responsibility before the end of the conflict.

Most scholars believe there is a need for an international establishment of jus post bellum criteria that will ensure that lasting peace is achieved post-conflict. Additionally, McCready, Orend (2007), and Iasiello (2004) agree that there should be a plan of action for post-war actions; Orend, Iasiello, and Boon (2005) advocate for ensuring accountability for unethical actions during conflict; Orend, Iasiello, and Bass (2004) stipulate some sort of compensation and or reconstruction aid post bellum; and Orend, Boon, and Kant (2006) recommend fair or proportionate aid and agreements.� Wars are inevitable and after a war has ended, there could be widespread suffering and destruction; both victor and defeated have responsibilities to restore the state�s essential services, transition to peace, and end suffering. �Jus post bellum introduces frameworks to develop treaties that could address these problems.

Kant introduced jus post bellum framework in 1796 in the Metaphysics of Morals (Stahn, 2006).� However, the international community views jus post bellum as an essential part of jus ad bellum and jus in bello (Anderson, 2014).� It only gained more consideration in the 2000s, possibly due to the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.� Since cyberspace is a new domain, much of the focus about cyberspace has been in the jus in bello and jus ad bellum as emphasized by the Tallinn Manual and the ICRC.� Nonetheless, works by Giesen (2013), Denning and Strawser (2014), Rowe, Garfinkel, Beverly, and Yannakogeorgos (2011), and Liaropolous (2010), discussed below, can be used as a basis for analysis of cyberspace jus post bellum and the creation of a cyber jus post bellum framework.

Giesen (2013) agrees that customary law and the UN Charter are applicable to cyberwar for jus ad bellum and jus in bello, but not for jus post bellum. �Giesen states that cyberspace is now a global common, the center of gravity, and societies are dependent on it, which means any threat against it can be debilitating. �Therefore, Giesen advocates for a new international treaty for cyber jus post bellum implementation based on the Kantian jus post bellum. �Giesen uses two criteria for an ethical cyberwar jus post bellum for the consequences of committing a war act, which consist of agreement violations that can disserve all people and conduct that makes peace impossible.� She advocates an international agreement that bans any cyberwar act that will cause enough detrimental �economic and social damage� that peace will not be possible. �She focuses on the prevention of cyberattacks rather than the actions after an attack was conducted or the war has ended, a deterrence approach to cyberwar such as with nuclear weapons.

Giesen�s approach is similar to Geib and Lahmann (2012) who advocate for the protection of critical civilian cyber infrastructure. �Article 56 of Additional Protocol I to Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 (API) (1977) outlines protected sites such as dams and dykes but also provides some stipulations that will allow a military force to target these.� The international community could add critical cyber infrastructure to the protected sites list or an international agreement could be signed banning attacks on certain critical cyberspace targets. �In addition, the repercussions of such cyber acts on such targets will need to be made sufficiently great to aggressors and guidelines for investigation and indicting infringers will need to be established.

Denning and Strawser (2014) advocate for cyber weapons use instead of kinetic weapons after the cyber weapon meets the jus ad bellum and jus in bello criteria.� They argue that using cyber weapons can pose less risk to both friendly and adversary military and non-combatants. �Denning and Strawser also argue that the use of cyber weapons can aid in the jus post bellum phase during stability and reconstruction. �Their main argument in the reconstruction phase is that the lethality or permanent damage of cyber weapons is low. �Therefore, the reconstruction phase will consist of restoring data from backup files, which will be faster than having to rebuild infrastructure after a physical attack.� It might seem like Denning and Strawser are contradicting Giesen�s proposed ban of cyber weapons.� That is not the case, as the only time they are advocating for the use of cyber weapons in place of kinetic weapons will be dependent on the ability of the cyber weapons to have results that are more ethical.

Rowe et al. �(2011) propose an international agreement similar to chemical weapons.� The agreement would outline when states can use cyberattacks, it would require states to police cyber criminals, and it would stipulate which cyber weapons are acceptable.� They argue that cyber arms control is possible now more than ever due to the increasing capabilities of forensic tools and the ability to observe cyberattack development.� An acceptable weapons agreement would mandate the use of only attributable and reversible attacks and a state could use digital signatures with a cyberattack to establish attribution. �An example of a reversible cryptography attack, as proposed by Rowe (2010), is �where the attacker encrypts data or programs to prevent their use, then decrypts them after hostilities have ceased.� �States will be encouraged to use reversible attacks if they are responsible for reparations on the attacked state and states understand that other cyberattacks can damage their reputation. Reversible attacks can also limit the escalation of force and satisfy the appropriate use of force. �These revisable attacks will make it easier to restore systems to their original state. �The biggest obstacle, they see is attribution due to states� not taking ownership of cyberattacks.

Liaropolous (2010) defines jus post bellum criteria based on the widely accepted Orend framework: Proportionality, Rights Vindication, Discrimination, Punishment, and Compensation.� However, Liaropolous does not actually define how Orend�s criteria apply to cyberspace.� He argues that even though it might seem like waging war through cyberspace is more ethical and result in fewer casualties, it would not necessarily be the case. �That is because a cyberattack can destroy public services such as electricity, transportation, and water, and possibly even paralyze a technical city, which will directly target critical infrastructure (Liaropolous, 2010). �In addition, Liaropolous warns that due to the blurry escalation of force in cyberspace, the result can be a �bloody war� with more casualties that were supposed to be avoided.� Therefore, Liaropolous advocates for the need of conventions to outlaw the development of cyber weapons that can be used as weapons of mass destructions.

All these scholars agree in the basic principles of creating some sort of cyber agreement for the use of cyber weapons and the outlawing of indiscriminate cyber weapons to stop cyber actors before they conduct a detrimental cyberattack.� These agreements will focus on deterring cyber actors by having severe consequences for any violation. �Additionally, critical infrastructure can be added to the protected sites and only cyber weapons proven to be more ethical should be used to limit human suffering and facilitate reconstruction post bellum.

As new atrocities occurred during war, the international community through the UN, ICRC, and other parties introduced new treaties, conventions, charters, and declarations to control armed conflicts and the subsequent peace. �The basic principles of Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC) include distinction, proportionality, military necessity, and humanity (Carr, 2011). �One important thing to note is that LOAC is often developed in response to incidents and to ensure they are not repeated. �For example, in 1977, the ICRC added the API that includes further protection for civilians and civilian objects during warfare, but only 174 countries have ratified it (ICRC, 2014).� This API specifies in Article 51 the protection for civilians from being military targets and Article 52 affords the same protection for civilian objects.

The UN charter (1945) does not specify anything about the LOAC as its main purpose is to maintain peace.� Still, the UN passes resolutions to protect civilians, such as UN resolution 2675 in 1970.� This resolution specifies that during �the conduct of military operations, every effort should be made to spare civilian populations from the ravages of war, and all necessary precautions should be taken to avoid injury, loss or damage to civilian populations� (UN, 1970).

As mentioned earlier, these international laws are mainly for jus ad bellum and jus in bello; nevertheless, some agreements do have post-conflict stipulations.� The following treaties and charters extracted from the international law convey the range of stipulations about jus post bellum. �For a more complete list of current international treaties, refer to Appendix A which lists current international treaties including the established date, number of state parties and signatories, main purpose, and the possible applicability to jus post bellum.� ICRC (2014) is the source providing the following information for the listed international treaties, unless otherwise stated.

�These conventions define the provisions for war declaration, belligerent conduct during war on land, the prohibition or restrictions of certain weapons and capturing in naval war, the conversion of merchant ships to warships, and the protection of hospital ships, neutral states, undefended locations, and cultural property. �These conventions �embody customary international law�; as such, violators are to be prosecuted for war crimes after the termination of hostilities. �After conflict, cultural property is to be returned, restitution made, and assistance provided for recovery after the conflict ends. �In cyber-warfare, the establishment of neutral powers makes their territory impenetrable.

These conventions afford protection to the wounded, sick, medical units and personnel, chaplains, voluntary aid, civilians and personnel not taking part in hostilities, victims of international and non-international armed conflict, medical material and locations, shipwreck, and hospital ships. �It also prohibits perfidy, provides guidelines for treatment of POWs, and facilitates the identification of protected personnel. �Violations of these conventions are prosecutable under war crimes after the end of hostilities. �Belligerents are to release and return POWs at the conclusion of the armed conflict.� In cyber-warfare, the prohibition of perfidy can be an issue as many attacks can involve impersonation.

These conventions prohibit the use of weapons that cause excessive injury or have indiscriminate effects.� Furthermore, additional protocols prohibit the use of weapons that produce undetectable fragments with x-ray and lasers causing permanent blindness, provide restrictions on the use of mines, booby-traps, incendiary weapons, and minimize �risks and effects of explosive remnants of war.� �Violations of these conventions are also prosecutable under war crimes after the end of hostilities. �Additionally, states are responsible for marking, clearing, removing, or destroying �explosive remnants of war in affected territories� in attempts to protect people from additional harm.

The Declaration Concerning Asphyxiating Gases prohibits �the use of projectiles [that] the sole object�is the diffusion of asphyxiating or deleterious gases� and the Convention Statutory Limitations to War Crimes �established no statutory limitation for war crimes and crimes against humanity.� �Violations of these conventions are also prosecutable under war crimes after the end of hostilities.

The declaration on the Prevention on the Convention and Punishment of Genocide establishes genocide as an international crime during peace and war. �Violations of genocide are prosecutable under peace and war crimes.

The Organization of African Unity Convention on Mercenaries provides guidelines to end mercenarism and calls for post-conflict prosecution and extradition. �Furthermore, the Convention on Mercenaries makes the recruitment, use, financing, and training of mercenaries prosecutable.

�The Convention on the Rights of the Child is aimed at protecting children and calls for the recovery and reintegration of children post-conflict.

The UN currently has 193 members (UN, 2014) bound by the UN Charter (1945) containing several articles that apply during jus post bellum or after an attack has been conducted. �However, a state must first infringe the peace or commit an act of aggression. �Therefore, through the UN General Assembly Resolution 3314 (1974), the UN defined an act of aggression and allows the UN Security Council freedom to determine if any particular act is considered an act of aggression.

Under this article, the UN Security Council bears response responsibility for �threats to peace, breaches of peace, and acts of aggression.� �The UN can use Article 41, which includes measures such as sanctions that do not involve armed forces, and or Article 42, which includes the use of an armed force, to respond to the armed attack.� Even though what constitutes an act of aggression or armed attack in cyberspace is still being debated, this article is important due to the requirement of UN response after an attack has been conducted.

�This article allows states to defend themselves against armed attacks and gives states the right to respond when under attack.

This article establishes the ICJ as the judicial body of the UN. �The ICJ articles relevant to jus post bellum are discussed below.

This article stipulates that states will comply with the decisions taken by the ICJ. �This means that after the ICJ has ruled on a case brought to it, the member states must abide by the decision.

The UN Charter (1945) established the ICJ as the judicial body of the UN.� Disputes and war crimes between states are brought to the court and under article 94, mentioned above, states are to comply with the court�s verdict.

This article establishes the court�s jurisdiction about �the interpretation of a treaty; any question of international law; the existence of any fact which, if established, would constitute a breach of an international obligation� (ICJ, 2015).� In addition, the court decides �the nature or extent of the reparation to be made for the breach of an international obligation� (ICJ, 2015). �This means that the ICJ has the power to apply law and issue verdicts.

This article stipulates that the court will apply international conventions and customary law to matters submitted to it (ICJ, 2015). �This article gives the ICJ leeway to determine if acts not explicitly outlined in resolutions or treaties are violations.

This article gives the court the power to issue measures to protect states� rights (ICJ, 2015). �That means that the ICJ can issue a mandate to protect states.

The Rome Statute established the ICC in 1998 and 154 states are parties to the ICC, but not the United States (ICRC, 2014). �Unlike the ICJ that settles matters between states, the ICC settles disputes against individuals and organizations (ICC, 2014) and exercises authority over severe �crimes of international concern� (ICC, 1998). �During jus post bellum, the ICC can settle violation disputes. �Under Article 5, the ICC has jurisdiction over crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, crimes committed during war, and acts of aggression.� War crimes refer to violations of the Geneva conventions and international LOAC.

The North Atlantic Treaty (1949) is an international agreement and under Article 5 reserves the right of member states to respond in an individual or collective way to acts considered armed attacks. �The response can include the use of an armed force and requires UN Security Council notification.� The response is to cease once the UN Security Council has taken steps �to restore and maintain international peace and security.� NATO is one example of an international organization that has agreements for collective response.

In conclusion, the majority of IHL, international

customary law, treaties, charters, and so on are concerned with the right of

states to go to war and stipulations to fight wars ethically. �The main

consideration for the aftermath of war is the prosecution of war crimes and

deterring actors with prohibition agreements and treaties. �Nonetheless, these

agreements can be used as an example to develop a new treaty for ethical cyber-warfare

jus post bellum. �For example, these international agreements already ban

indiscriminate weapons before they are used, which would include indiscriminate

cyber weapons, and mandate respect of neutral territories. �In addition, the

frameworks and ideas presented by the discussed theologists, scholars, and

ethicists can aid in the creation of a cyber jus post bellum framework for an

ethical transition from war to peace. �A treaty outlining the jus post bellum

criteria for cyber-warfare will be beneficial for the international community.

Policy makers need a basic understanding of the different types of cyberattacks: the feasibility of conducting cyberattacks through different vectors, their effects, ways of establishing attribution, and the ability to contain and reverse them.� This will aid policy makers in generating correct policies and international agreements to deal with the aftermath of a cyberattack.� In the same manner, an understanding of cyberattack characteristics and effects will help develop correct post-cyber-conflict actions.

News of cyberattacks is an everyday occurrence around the world.� It is evident by news stories of cyberattacks to steal money, information, and intelligence, break computer systems, modify information, and or make information inaccessible to legitimate users.� There is a huge cost associated with responding to cyberattacks on information systems, which includes assessing the damage, attempting to establish attribution, and restoring systems and information.� For example, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) estimated that botnets have cost U.S. victims losses totaling 9 billion dollars (Demarest, 2014).� Not all these attacks constitute an act of war; in fact, no single attack to date has been agreed by any consensus to be an act of war.� These attacks have generally been categorized as criminal and have been costly.� However, some of these cyberattacks were state-on-state and could have been considered an act of war.� Cyberattack is a broad term because it encompasses low-level attacks and major attacks by any entity.� Therefore, there should be a distinction between cyber act of war and other cyber activities.� The distinction can be made in international agreements, with the understanding that to be categorized as a cyber act of war, the attack would have to meet a designated list of criteria.� For example, Schmitt (2013) defines a cyber act of war by these criteria: severity, immediacy, directness, invasiveness, measurability of effects, military character, state involvement, and presumptive legitimacy.

Even though there should be a distinction between a cyber act of war and other cyber activities, aggressors in cyberspace use the same methods to develop and carry out cyberattacks. �These actions usually include deciding on a target, establishing goals, conducting reconnaissance, deciding on the type of attack and attack vector, and carrying out the attack.� Cyber criminals focus on financial gain and do not give too much thought to possible collateral damage.� On the other hand, state actors should be more concerned with developing cyber weapons that can be contained or reversed and can achieve the same objectives, which would limit human suffering, collateral damage,� and further public�s acceptance and trust.� Developers could check this through careful testing of the cyber weapon on target and non-target systems to ensure it has the desired effects.� Cyber-weapon developers must be able to determine if the deployed weapon will meet the desired effects, and determine cascading effects, to inform the decision makers of cyber-weapon deployment consequences.

States design cyber weapons to accomplish different effects depending on the desired outcome, unlike a kinetic weapon used mainly to destroy a target.� The cyberattacks on computer systems affect confidentiality, integrity, and or availability. �This section provides a description of various cyberattacks and their usage to achieve military objectives.� It is important to note that technical expertise and financial backing are limiting factors for cyber-weapon development.� However, there are cyberattacks readily available for a price that can cause damage without much technical knowledge, which enables non-state and developing states to use cyber weapons too.� Paramilitaries and militaries can use publicly available cyberattacks, modify them, or apply their own developed malicious codes, to disrupt, destroy, deny, and degrade an enemy to obtain the military advantage.

Denial of service (DoS) and distributed-DoS (DDoS) are cyberattacks that target availability of computer systems to legitimate users.� Aggressors would use one or multiple systems to swamp an Internet-connected system with data to render it or its resources unavailable (Schmitt, 2013).� A military unit can use this attack to prevent communications or make air-defense systems unavailable during a military operation.� According to Ponemon Institute (2013), DoS attacks are the most costly type of attack due to their frequency.�

However, most attacks involve malware.� Malware is malicious code that has negative effects on computer systems.� Aggressors develop the code and deliver it through �attack vectors�.� Aggressors embed malicious code in software, firmware, and hardware; examples include logic bombs, rootkits, viruses, and worms (Schmitt, 2013).� A military unit can use malware to destroy systems, delete data, or spy on their enemies.� The Ponemon Institute (2013) reported an average of 49.8 days to resolve malware attacks, which equals an average cost of over 1.5 million dollars per incident.�

An Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) consists of an aggressor that was able to gain access to a system and established a foothold into the system.� APTs use various methods, as depicted in Figure 1, to break into computer systems while remaining undetected to gather intelligence or conduct other types of activities (Symantec, 1995). �Military units can establish APTs to set up future sabotage activities.

Figure 1. Advanced Persistent Threat (from Symantec, 1995).

Attack vectors are the method, people, or vessels by which cyber actors deliver cyberattacks.� Aggressors decide on attack vectors in conjunction with the attack type and it can depend on the target�s cyber-security posture.� For example, an organization with out-of-date patches is an easier target for access exploits, as vulnerability lists and exploits to those vulnerabilities exists all over the Internet.� Aggressors are able to determine devices� operating systems and versions during reconnaissance, which helps them determine the method of delivery.� Attack vectors also facilitate targets of opportunity.

Social engineering often involves the use of deceptive emails, Webpages, and links that entice a target to unknowingly download malicious code.� Social engineering includes phishing (mass emails), spear phishing (targeted emails), and whaling (executive-target emails).� These attack vectors are commonly used because they are very successful with large groups of people (Kevin Mandia, Presentation, March 26, 2014).� This means that at least one of the targets will click or download the malicious file, giving the attacker an access point into the targeted network.� Social engineering can be the first step in either establishing an APT, logic bombs, or botnets.

Malicious insiders are personnel within an organization that are willing to aid an aggressor.� Silowash, Cappelli, Moore, Trzeciak, Shimeall, and Flynn (2012) defined a malicious insider as someone who had or has legitimate access to information and deliberately performed acts that targeted the organization�s confidentiality, integrity, or availability.� Malicious insiders have the ability to cause more damage than other aggressors because they not only have access to the systems but they know more about the targeted system�s vulnerabilities.� Aggressors can recruit and use malicious insiders against air-gapped systems such as air-traffic control.

Botnets are networks of compromised computer systems directed by an aggressor to carry out coordinated cyberattacks (Schmitt, 2013).� Computer systems in botnets are usually unwilling participants that augment the aggressor�s ability to conduct cyberattacks.� Aggressors use botnets to enhance DDoS attacks or as pivot points to hide their tracks.

Zero-day attacks refer to newly discovered vulnerabilities and are the most difficult attack vectors to develop and discover; they require higher technical knowledge because they involve finding an unknown system flaw or vulnerability to introduce the malicious code.� The software vulnerabilities are unknown to software developers and vendors (Zetter, 2011) and hence they are hard to counter.� Symantec reported that there is less than one zero-day exploit out of the one million malware samples they receive per month (Zetter, 2011), which demonstrates the rarity and difficulty of finding zero-day vulnerabilities.

Removable media, such as universal serial bus (USB) drives, could be used by a malicious insider or unwilling participant to inadvertently introduce malicious code if the removable media was not properly scanned before plugging it to the network.� Other types of removable media that can transfer viruses include laptops, writable compact discs, and tablets. �For example, Zetter reports that the attack vectors used to deliver the Stuxnet worm against Iran were an infected USB thumb drive and a malicious insider.� Unknowing participants can also deliver malicious code through USBs, as in 2009 in the United Kingdom with the Conficker worm which resulted in over 15 million worldwide infected computer systems (Whittaker, 2013).� Even after these incidents, Whittaker reports that U.S. Department of Defense continues to allow these devices on secure system to expedite work processes instead of security and policy adherence.

This section will discuss three cases: Estonia (2007), Georgia (2008), and Iran (2010) to illustrate the different effects cyberattacks can have on systems, infrastructure, and civilians.� In addition to these cases, the Sony Pictures Entertainment (SPE) hack will be discussed below and in a later chapter as these attacks are a good example of state-sponsored attacks.� The effects can be physical, economical, and or social with excessive collateral damage.� Even though no one has categorized these cyberattacks as armed attacks, the cases highlight the disregard for Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC) adherence seen in cyber-warfare-like attacks, especially in targeting civilian entities and infrastructure.� In addition, states are legally and morally bound by LOAC whether they are taking part in hostilities or not.�

In 2007, in response to relocating a Russian bronze-soldier war memorial, Estonia suffered cyberattacks for over a month (Kaska et al., 2010).� The targets were government e-services Websites, banks, Internet infrastructure, and media outlets.� Estonia�s big Internet footprint and attack coordination made the attack more powerful and successful.� Coordination of times, target lists, and instructions on how to carry out the attacks were made available to the public; therefore anyone with a connection that wanted to contribute could contribute.� The attacks grew in intensity and sophistication, starting with ping requests, then later used malformed Web queries and botnets while hiding their identity though proxies and Internet Protocol (IP) address spoofing.� Aggressors use proxies and IP spoofing to mask the attack origin.� The botnets� command and control were placed in locations that would not cooperate with investigations, which highlighted the need for international agreements on cooperation, investigations, and prosecution of cybercrime and cyber-warfare.� 95�97% of Estonians conduct online banking, so these cyberattacks damaged the Estonian economy because the ability for all businesses to function was stopped, even though total losses have not been reported.� These attacks also had negative social effects since Estonia�s primary means of communication between citizens and government is through the Internet.� Even the information coming out of Estonia was severely restricted.� Kaska et al. qualified these events as being in a higher category than cyber crime, yet Estonia only prosecuted one person for these attacks.

In 2008, Georgia was the target of cyberattacks coupled by kinetic Russian attacks (Kaska et al., 2010).� Schmitt (2013) argues that since these cyberattacks were part of hostilities, LOAC should have governed them.� Just as with Estonia, the targets included governments, news and media outlets, and financial organizations (Kaska et al., 2010).� Making civilian organizations primary targets is the reason Schmitt argues that these attacks were in violation of LOAC.� The attacks were coordinated and included botnets, DoS, DDoS, Web defacements, and e-mail spamming (Kaska et al., 2010).� The DoS and Web defacement are easy to repair (Rowe, 2010), still these attacks were unethical because the Georgian Government was unable to communicate with its citizens (Kaska et al., 2010).� This exemplifies another case where possibly a nation-state targeted civilian organizations and should be held accountable post-conflict for actions conducted during conflict.

In 2010, a Belarus security organization discovered the Stuxnet worm that had targeted the Natanz nuclear facility (Zetter, 2011).� Symantec analysts believe the attack was to prevent Iran from building their nuclear weapon arsenal.� The attack used malware against a Siemens industrial-control system and its vectors were zero-day vulnerabilities, a USB, and a malicious insider.� The attack affected thousands of centrifuges and it was the first time that there was an observable physical reaction from a cyberattack.� This cyberattack shows the secondary physical effects a cyberattack can have through code manipulation.� Antivirus organizations updated and distributed prevention signatures, and even then, over 100,000 computer systems suffered collateral damage.� Antivirus organizations can do as much as possible to prevent further computer infections, but some malware has the ability to evade those protections.

Because of the excessive damage cyberattacks can cause, cyber operations need to follow an operations-planning and targeting process to vet and validate legal targets and methods of attack.� States would be in violation of LOAC if civilians are primary military targets without a strategic significance (Rowe, 2010), which has been the case with various cyberattacks.�� Cyber operators must be able to determine if the deployed weapon will meet the desired effects while taking in consideration LOAC limitations, such as prohibitions on indiscriminate weapons and on making civilians or protected objects primary targets.